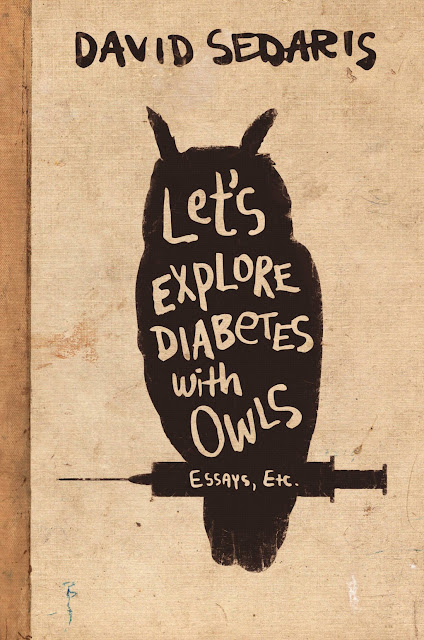

BOOK REVIEW: David Sedaris, "Let's Explore Diabetes with Owls"

The moment I heard that David Sedaris’ new book of

essays, Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls,

was scheduled to arrive this year, I literally cackled with glee. I first discovered Me Talk Pretty One Day, arguably his best work, in 2007 and have

since eagerly gulped down all of his collections of humorous essays. Sedaris’ wry looks at his family and the

world around him have consistently made me laugh aloud while reading, a rare

feat from an author. For better or for

worse, he spares no one, including himself.

Let’s Explore Diabetes with Owls, unfortunately, fails

to reach the same levels of pure ecstatic humor of the best of his previous

efforts. The pieces of the puzzle are

all there—some essays handling his odd family; a few devoted to his life in Europe

with his longtime boyfriend Hugh, whose personality is revealed more in this

book than in any of Sedaris’ previous efforts; and some intermingled character

studies in which he creates entire conflicts with bystanders all in his

head—but they fail to add up to the same level of quality I had been

expecting.

(davidsedarisbooks.com)

It’s when Sedaris attempts to address issues such as

race that his typical self-effacing yet self-absorbed style left me uncomfortable.

This issue is particularly evident in “A

Friend In the Ghetto”, where the author reveals, via a frame narrative, that

even in later life, his narrow-minded, privileged, white-savior mindset about

race hasn’t changed much. The story

opens with a call from a telemarketer in the present day who Sedaris imagines

has a voice with “snakes[…]dysentery[…]and mangoes” in it and with whom he

wants to talk again, if only to learn about the desperate poverty he imagines

the telemarketer endures (“an old refrigerator beside a drainage ditch” as a

home). He then relays the story from his

childhood in North Carolina, with the advent of integration in schools, when he

pretended to date an outcast black girl (whose name he does not remember) to

make his white family feel uncomfortable, imagining her to be “virtuous” and

humble by nature. What the author

reveals through this unpleasant vignette is that people of color and the less

fortunate remain mere props, examples to make him feel better about his life,

which he readily admits but shows no sign of remorse or regret about. His tendency to think of nearly every person of

color he comes across as some kind of starving, oppressed saint or person eager

to be saved is becomes grating.

Another chapter, in which he eviscerates the entirety

of Chinese cuisine, is similarly painful to read in this regard; this

particular episode has been criticized for this reason by other reviewers. This volume reveals a Sedaris who has grown

meaner and who has sharpened his edges with age. Thus the ensuing contrast of stories like “A

Guy Walks into a Bar Car”, when he describes with a certain tender air the

events that led him to first give Hugh a call, is all the more glaring. Clearly, if you get on his bad side, you’re

likely to stay that way, and to be railed against on the page—and even those he

loves are not entirely safe.

Sedaris,

curiously enough, devotes a chapter that seemingly obliquely addressed the

criticism he has faced over the embellishment of his essays, and their

challenged statuses as works of nonfiction. His humorous essays, it seems, are too good to be true. In a piece titled “Day In, Day Out”, he chronicles his longstanding

habit of diary keeping and how his entries have changed over the years. Nowadays, he writes down small snippets of scenes he

observes, using them as fodder that he then expands into polished essays he can

hopefully read to live audiences, on the radio, or send to publications. In one particular example, he chronicles how

while he wrote down a particularly odd exchange between a woman and a young

girl, he regrets that he didn’t take more time to describe their clothing and

various other physical details. In this

way is Sedaris perhaps offering a mea culpa about his process, or is he

challenging the same critics who condemn his embellishments. If he can’t remember every detail of every

encounter he has or observes, he seems to argue, why not embellish, and make a better story?

Sedaris also pulls no punches when discussing his

long-suffering father, shedding more light in what seems to be a complex and at

times, frustrating and adversarial relationship. But with the light of his

heavy fictionalization in mind, do we really know Lou Sedaris at all via his

son’s writing through the years, or do we have only the most meager impressions

of him? Are we indeed learning more about Hugh’s

personality when, in an essay entitled "Rubbish", Hugh develops a nonsensical idea to reduce the litter that blights the roads of the couple's new home in the English countryside, or is it once again David's voice filtered through another

character in his life? In this regard,

the call for greater honesty, or at least, for a reduction of embellishment in

Sedaris’ essays has some definite weight.

Sedaris

is by now in his mid-fifties, yet, thankfully, his observations of the current

generation (of which I am a part) are warm and affectionate. He expressed gratitude towards his younger

fans on his last book tour, for example, by handing out condoms at book

readings. When he inevitably does mock youngsters,

he manages to be funny without being overly curmudgeonly.

Interspersed

throughout this book are short speeches the author wrote for students to use

during speech competitions, which are an interesting throwback to the short-form

fiction of Barrel Fever, his first

book. Unfortunately, these stories tend

to follow the same sort of pattern and contain wildly exaggerated depictions of

vile, selfish people. First these

speeches, which are all written in the first person, slap the reader in the

face with an outsize, impossible to love persona, and then the speech gradually

unfolds and escalates to reveal the often-cruel punch line. These people are all classical Sedaris caricatures,

people so comically villainous that they only could be born from his mind,

based no doubt on some negative encounter. One particular speech, however, in which

Sedaris inhabits the mind of man who goes on a murder spree in response to the

New York legislature’s legalization of gay marriage, is rendered rather

poignant when we consider the vitriol Sedaris has likely faced during his life

due to his sexuality.

Let’s Explore Diabetes

with Owls

(which explores owls but not diabetes), should not be missed by a true fan of

Sedaris’ work, but I would not recommend it to a reader new to the author. I will continue to point those readers

towards Me Talk Pretty One Day or Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim,

another higher-quality, more consistent effort.

Yes, yes, yes! I read this last month and felt the same sense of discomfort, especially with the anecdotes about Chinese cuisine.

ReplyDeleteHmm, that's a bummer. Maybe I'll skip this one. Could it be he's out of ideas?

ReplyDeleteI read the first essay and thought it was interesting. I will continue to read although with a different expectation after reading your review. I will say however, that perhaps his perspective on life is changing as he ages? Well written review...and it had to be tough to be critical because you are such a fan!

ReplyDelete